On September 3rd we had our second meeting of the Stanford Digital Humanities Reading Group, in which we discussed Matt Jockers’s new book, Macroanalysis: Digital Methods & Literary History. Because Jockers is a former colleague, a co-founder of Stanford’s Literary Lab, and a friend to several people in the reading group, I went into this meeting anxious that we might all be too happy with his book to sustain ninety minutes of conversation. I was very wrong. Jacqueline Hettel, whose Ph.D. research focused on text analysis of domain-specific language using corpus linguistics, prompted a vigorous debate about the methods Jockers uses in Macroanalysis. Hettel’s primary critique is that the statistical methods behind topic modeling, word frequencies, and other methods that undergird the book’s chapters are heavily dependent upon a set of assumptions common to NLP, Chomsky, and other primarily American approaches to understanding language.

Topic models, for example, rely on the assumption that Bayesian analysis can accurately describe how language works. When Jockers, in chapter 7 (“Nationality”) relies on the mean usage of the word “the”, he assumes that language has a Gaussian distribution. Hettel prefers a log-likelihood method, among others, owing to her training in the school of linguistic thought exemplified by her major professor William Kretzschmar, who follows John Firth and others in what is known as the “London School”. I am not a statistician nor a linguist, so it did not occur to me that the statistical methods Jockers uses might be controversial or, more importantly, that they make assumptions about the nature of language. This topic led the group to consider the purpose of the book, the audience, and its relationship to more traditional modes of literary scholarship. Is the evidence in support of Jockers’s argument meant to get at some truth, and hence tangled up with the problems of scientism, or, as Blevins asked, is the evidence he presents more akin to the sort we find in a close reading, where the force of argument is driven by a persuasive narrative?

Moreover, Jockers, whose Ph.D. is in English and who is a scholar of Irish literature, is not a linguist or statistician either. Was his use of tools like relative work frequencies, topic models, and part-of-speech taggers a conscious choice that reflects his understanding of the nature of language or an unconscious one borne of an ignorance of this other realm of quantitative studies of language? In using methods that edge so close to those that have been used in linguistics for a relatively long time compared to the newness of quantitative text analysis in digital humanities, Jockers prompts us to think about how such scholarship may overlap disciplines in which we lack enough expertise to even understand what our choices entail. Indeed, my uneasy truce with the use of topic models for literary analysis stems from my keen awareness of how little I understand about the assumptions behind Latent Semantic Analysis.

We must also consider the context not only of the language under study, a point Hettel emphasized, but also the context in which the methods were chosen. Perhaps owing to the work of Stanford’s Natural Language Processing group, led by Christopher Manning and Dan Jurafsky, Jockers was led when he began his work in this area towards tools like the Stanford POS Tagger and others that imply certain language models of which those of us using such tools are not fully aware.

We also touched upon the nature of classification in digital humanities, which Ted Underwood has written about recently on his blog. In Macroanalysis, Jockers regularly classifies texts according to genre, nationality, or gender, but one of these things is not like the others. Genre, as studies in neuroscience and cognitive literary theory have shown (and which is the topic of my own dissertation), is not a static box into which texts may be placed, but instead a network of associations more in line with Jauss’s “horizon of expectations”, which emphasizes the reader’s prior knowledge and the interrelated nature of features in literary works. There is little acknowledgement in Jockers’s book that genres possess an internal structure or that this structure is not accessible via machine-learning classification methods as currently deployed by digital humanists.

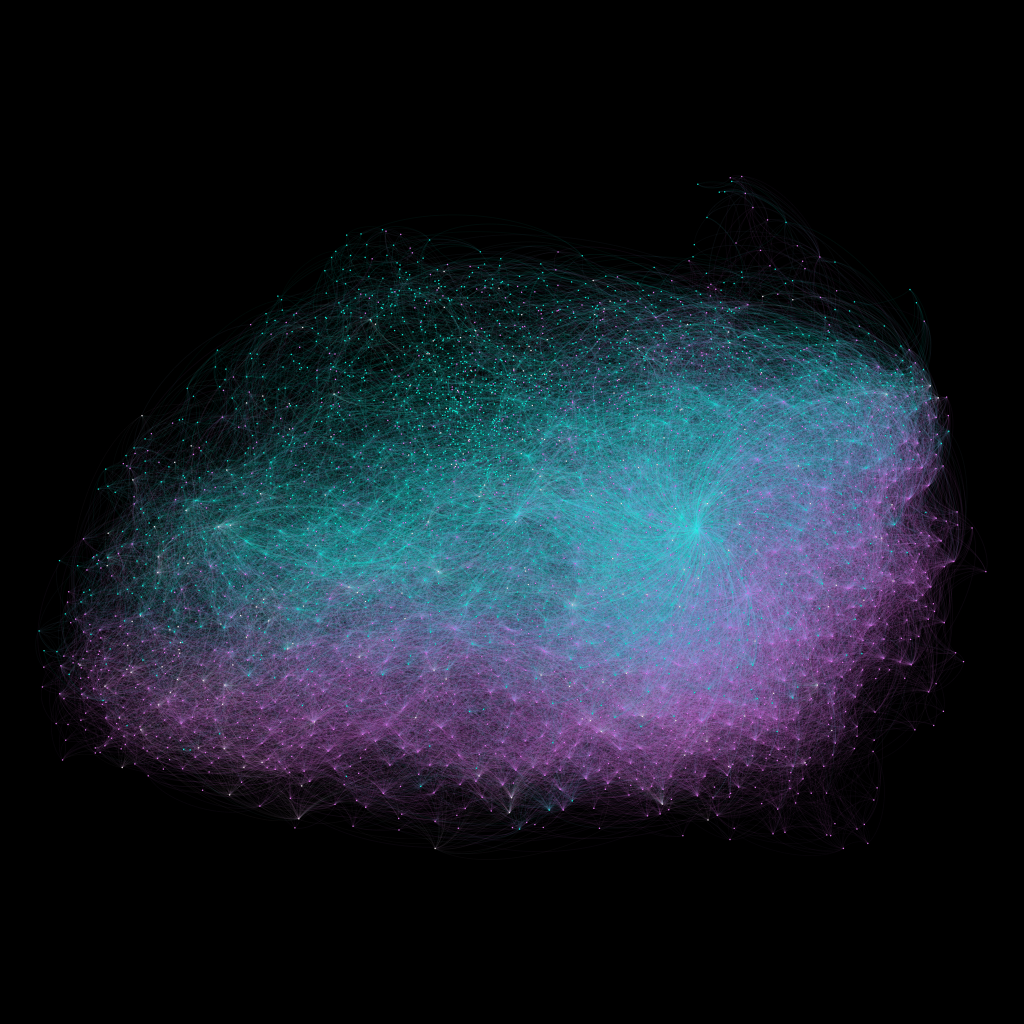

This objection returns us to the core question about the book’s audience and purpose. I have seen several people on Twitter note that they could use this book as something like a textbook for a digital humanities course. And, as Worthey rightly noted, Jockers does a masterful job of leading potential skeptics “by the nose” from simple, seemingly straight-forward (though still novel) analyses to the more arcane world of network graphs derived from topic models and stylometrics. I suspect that this book has in mind at least both the audience of skeptics and the already converted who want to know precisely what algorithms he used to derive his findings.

The book prompted an invigorating conversation that touched on these and other issues that, as digital humanities scholars, we should engage with regularly and critically. Our next discussion will focus on the collaboratively-authored 10 PRINT, a very different kind of book. If you are in the Bay Area and free that day, we invite you to join our discussion.

Attendees: Cameron Blevins, Jason Heppler, Jacqueline Hettel, Karl Grossner, Michael Widner, Glen Worthey

Reviews of Macroanalysis:

Mike Kestemont, LLC, http://llc.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2013/08/22/llc.fqt056.full

Scott McLemee, IHE: http://www.insidehighered.com/views/2013/05/01/review-matthew-l-jockers-macroanalysis-digital-methods-literary-history

Scott Weingart: http://www.scottbot.net/HIAL/?p=34566

Matthew Wilkins, LA Review of Books: http://lareviewofbooks.org/review/an-impossible-number-of-books/